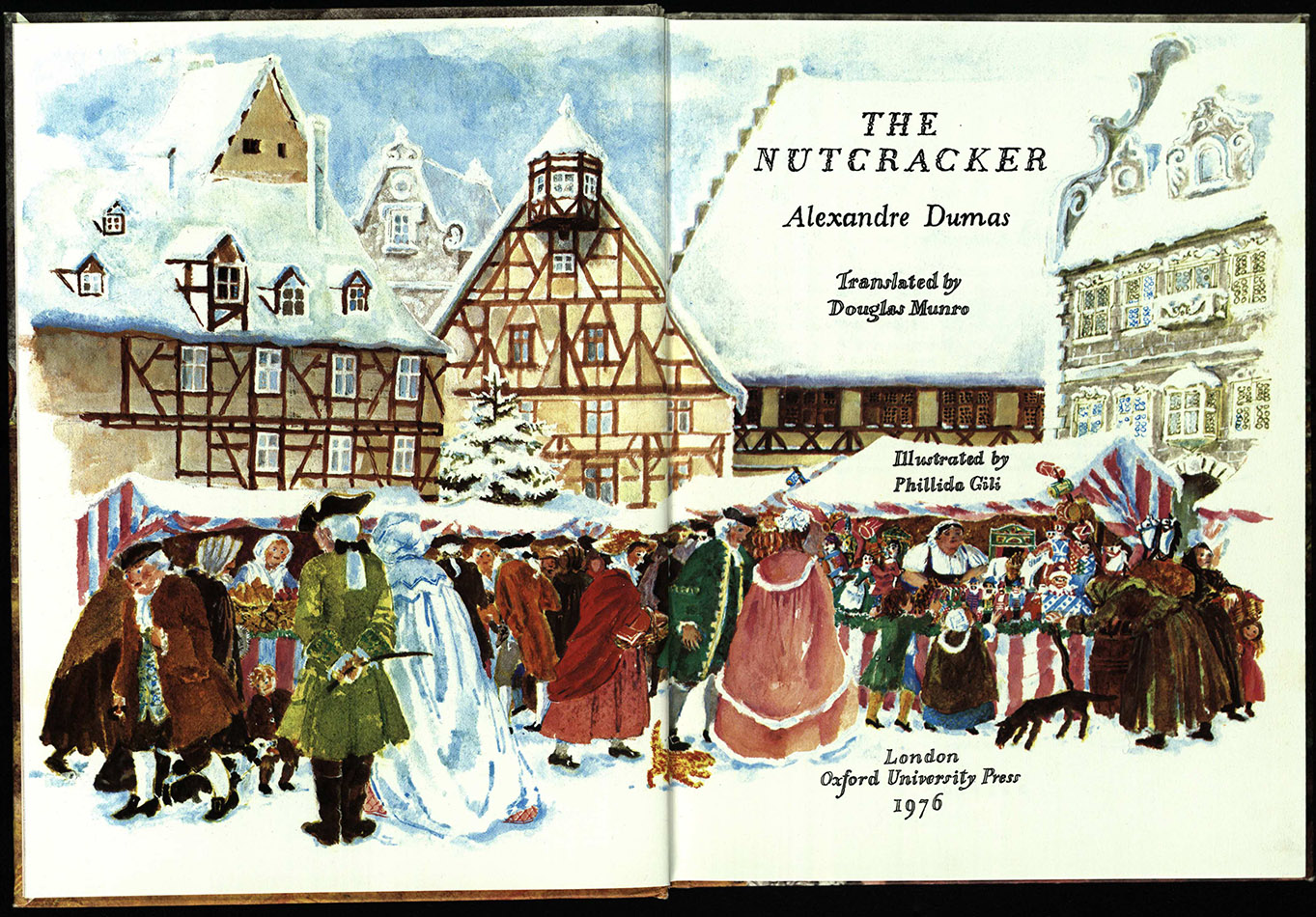

Reading the Collections, Week 41: The Nutcracker – a story for Christmas

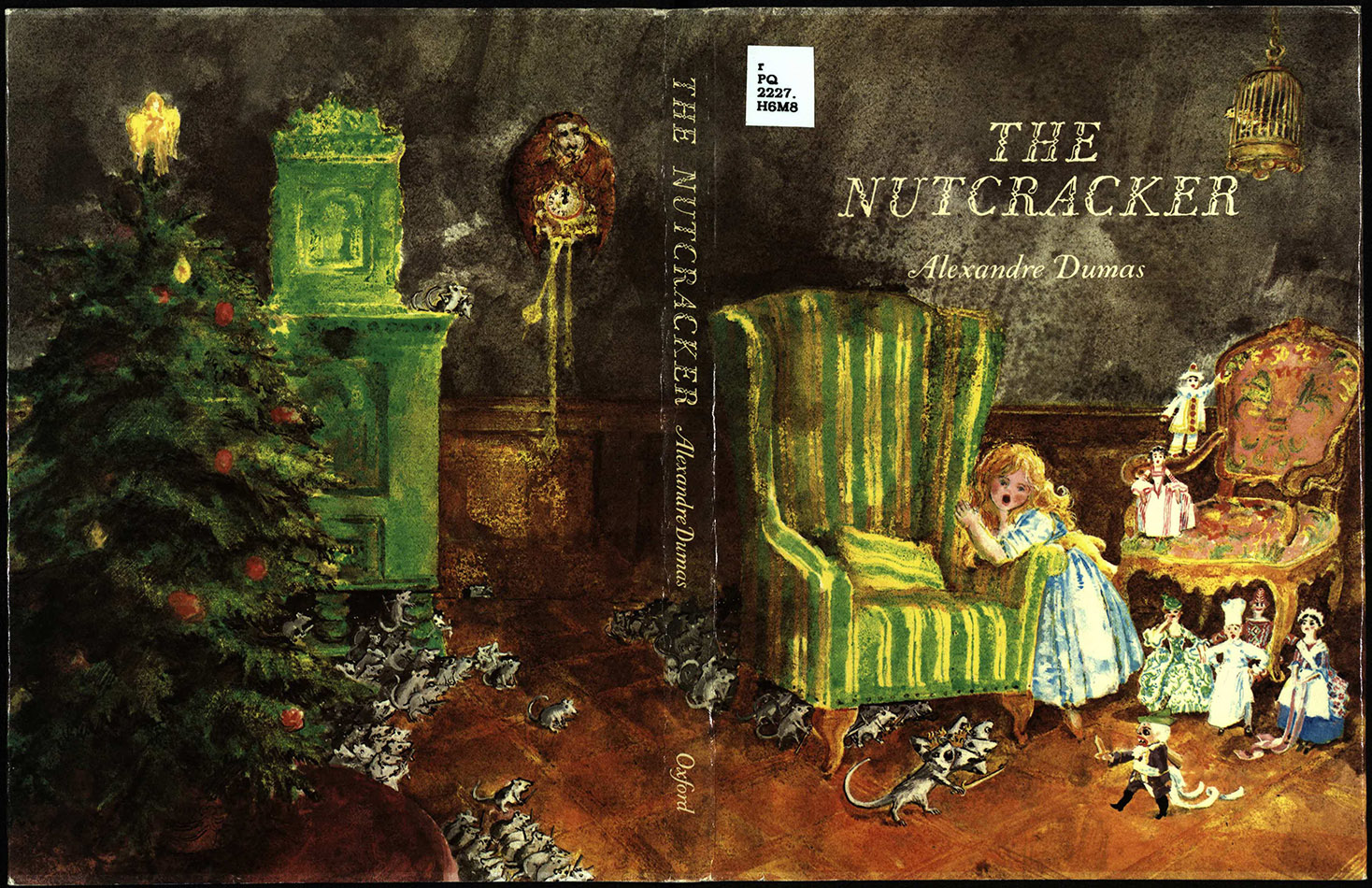

Whilst browsing the shelves one day, I noticed a book by Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870) – The Nutcracker. I was immediately intrigued, as I (perhaps foolishly) hadn’t realised that this tale was originally in book form. I was only familiar with Tchaikovsky’s ballet (and then only to the extent that it involved a nutcracker, and had the dance of the sugar plum fairy, a tune which must be familiar the whole world over).

The original tale, The Nutcracker and the Mouse King (Nussknacker und Mausekönig), was written by E.T.A. Hoffmann (1776-1822) in 1816. Hoffmann was a German Romantic author, whose works of fantasy and horror were very influential during the 19th century. The story was adapted by Dumas in 1844, under the title Histoire d’un casse-noisette, and it is this version, translated by Douglas Munro and illustrated by Phillida Gili, which we have in Special Collections (indeed, it was Dumas’ version upon which Tchaikovsky based his ballet).

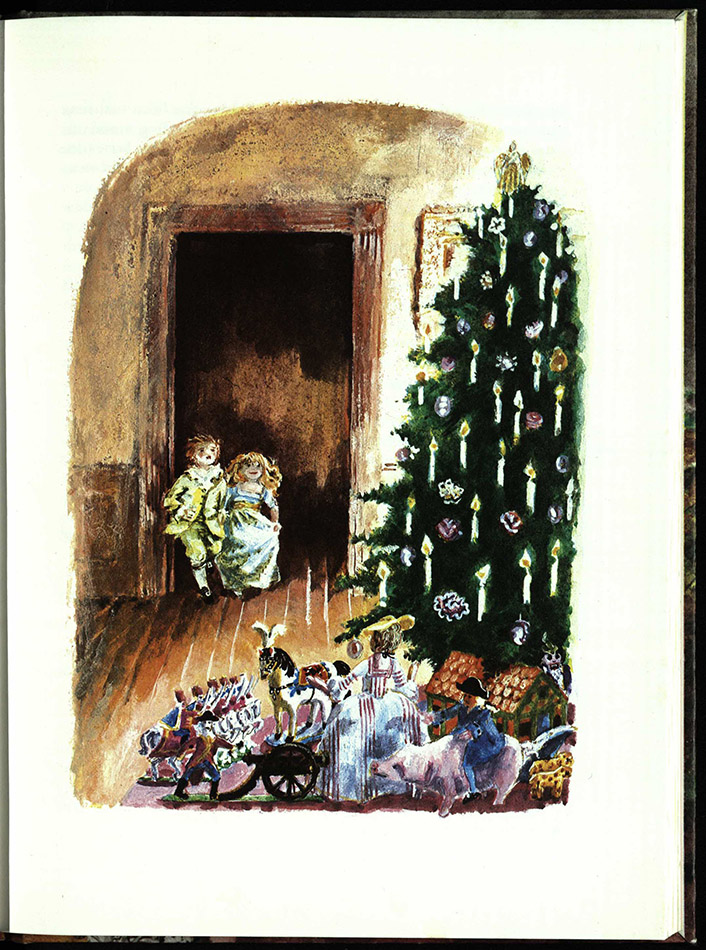

Knowing that the Nutcracker comes to life on Christmas Eve, I was expecting the story to be rather cosy – something eminently suitable for Christmas. Perhaps this is the influence of Tchaikovsky’s ballet, most often performed over the Christmas period, and which therefore has associations with warm, cosy feelings – nights in with a roaring fire, the smell of mince pies in the air, gingerbread decorations on the tree scenting the air….

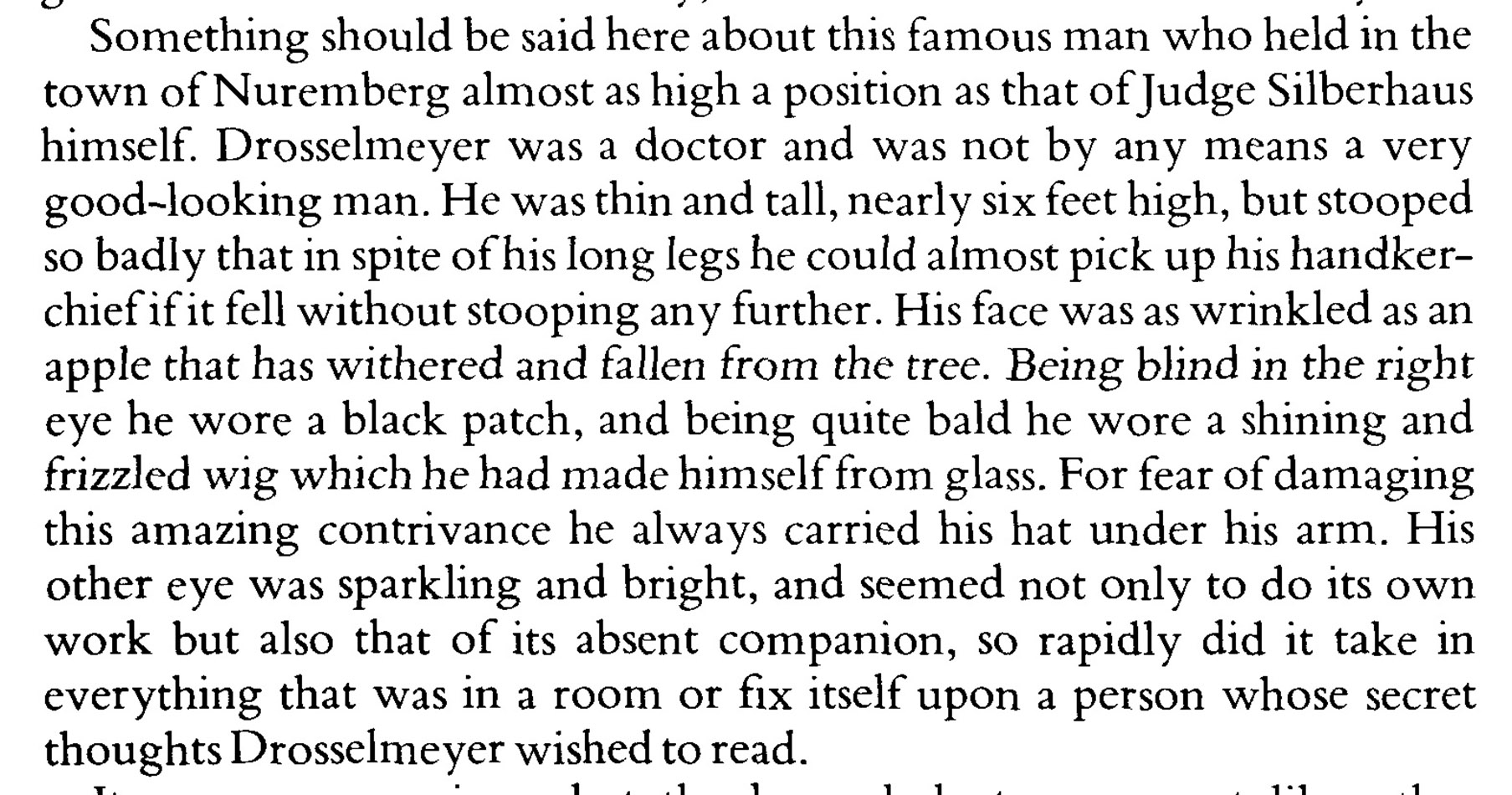

Whilst everything does ultimately turn out for the best, the Nutcracker, to my mind, is given something of a rather sinister cast in the first few pages. The child Marie notices his familiarity to her godfather, Dr Drosselmeyer, who is first presented as a wonderful adult who can make all manner of charming mechanical toys, but who, on closer inspection, appears to have rather a temper, and is certainly cast in the role of villain by his appearance:

As Marie very much loves her godfather, the Nutcracker, whilst ugly, has a charming face in her eyes. But after his jaw has been broken through cracking large nuts, when Marie mentions Dr Drosselmeyer’s name,

“the nutcracker made such a dreadful face, and his eyes suddenly flashed so brightly, that she [Marie] stopped short and stepped quickly back”.

If I’d been reading this late at night, I probably would have cowered under the bedcovers.

With only my memories of the ballet, this didn’t seem like the pleasant Nutcracker I remembered. But in the context of Dumas’ story, which includes the sub-plot of searching for the Krakatuk nut which reveals how Drosselmeyer lost his hair and eye, and that he was ultimately responsible for the Nutcracker being who he was, this reaction seems perfectly justified. But I run ahead of myself. For those, who like myself, are unfamiliar with the tale, here’s a brief summary.

Whilst recovering the next day her godfather tells her the story of how Princess Pirlipatine was cursed by Dame Souriçonne, the Queen of the mice, and that only the krakatuk nut could restore her beauty, which must be cracked and handed to her by a man who had never been shaved nor worn boots since birth, and who must, without opening his eyes, hand her the kernel and take seven steps backwards without stumbling.

Two men set out on this quest, one of whom is Drosselmeyer. After years of searching (and Drosselmeyer sustaining the loss of his hair and eye – if you wish to find out how, then read the book!), they return empty handed, only to find the nut in Drosselmeyer’s brother’s shop, and that his nephew is the man who can break the spell. Unfortunately for the nephew, upon his seventh step backwards he treads on Dame Souriçonne, and in her death-throws she transferred the curse from the princess to him, changing him into the ugly Nutcracker. The Princess then refuses to marry him and banishes him from the kingdom. Thus how young Drosselmeyer became the Nutcracker.

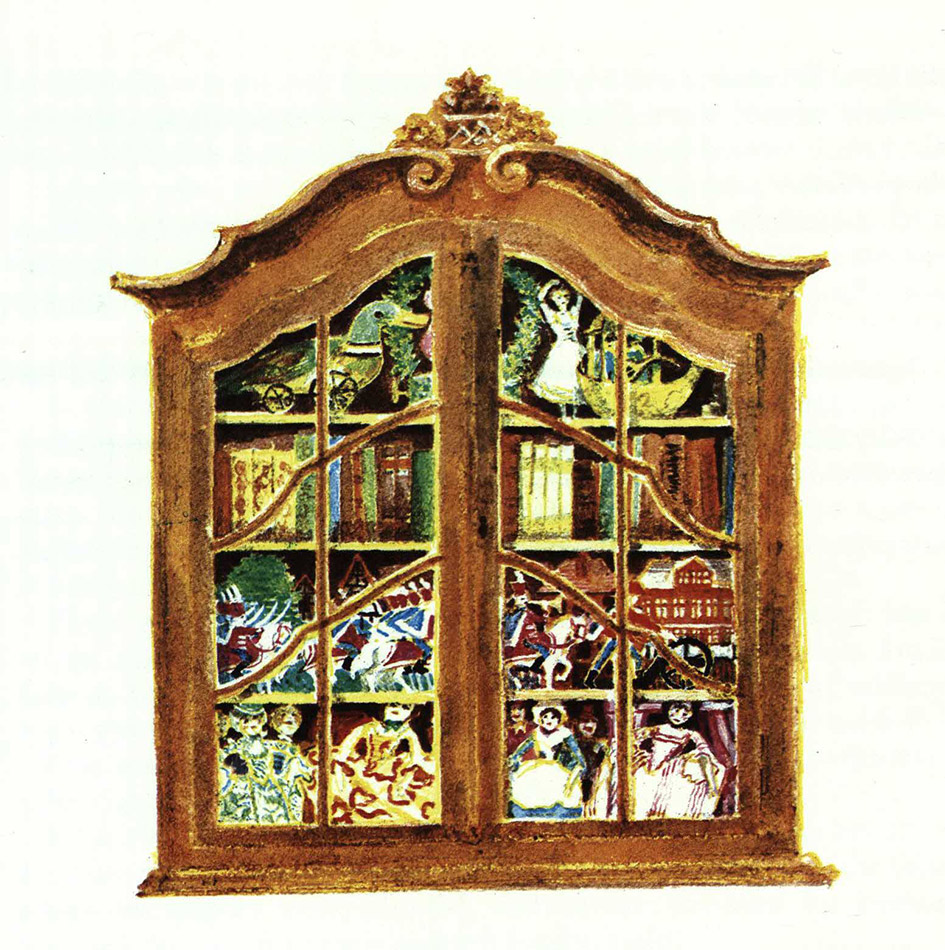

Back in the present setting of the tale, the king of the mice comes to Marie in the night, demanding sweets and dolls or else he’ll eat up the Nutcracker. Marie complies, but eventually the Mouse King wants too much, and the Nutcracker tells Marie that if she gives him a sword he’ll finish off the King. Fritz kindly gives her one of his major’s swords (the major being on half pay), and that night the Nutcracker defeats the king of the mice, after which the Nutcracker takes Marie to the kingdom of toys where everything is made of sweets. This is entered by climbing through the sleeve of a cloak hung in a large old cupboard – was this where C. S. Lewis got his idea from for the gateway into Narnia in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe?

Although Dumas ‘prettified’ Hoffman’s tale, setting out to soften the darker and more grotesque elements (Hoffman’s battle scenes are certainly more graphic), I still found elements of this story rather sinister – something I was not expecting from the tale. But I thoroughly enjoyed reading it, and having the opportunity to explore another genre by an old favourite (Dumas), and being introduced to a new author (Hoffmann). I shall certainly be reading more from both in the future.

-Briony Aitchison

Assistant Rare Books Librarian